To co jest mówione, jest jednym z najbardziej konkretnych przejawów naszych myśli, postaw i preferowanych sposobów działania – może zostać nagrane, przepisane oraz poddane rzetelnej i precyzyjnej analizie ilościowej i jakościowej. Badanie języka to nasza pasja i najbardziej podstawowa metoda pracy. Przejdźmy do kilku przykładów.

Analiza wypowiedzi

Psychologia języka

Analiza wypowiedzi

narracja i paradygmaty, rachunek zdań, części mowy, formy fleksyjne, FOXP2

Komentarze do Państwa wypowiedzi w raportach indywidualnych oraz przekazywane w czasie treningów wskazówki komunikacyjne mają najczęściej odniesienie do następujących dziedzin wiedzy i nauki o języku. Tutaj chcemy wymienić jedynie najważniejsze z nich.

A. Antropologia i początki rozwoju mowy

Człowiekowate - 99% rozwoju bez języka

Przyjmuje się, że język jaki znamy, tj. oparty na składni, powstał ok. 45000 lat temu wraz z pojawieniem się nowego gatunku Homo Sapiens. Przy 6 mln lat rozwoju hominidów mówienie jest czymś naprawdę nowym (to poniżej 1% czasu rozwoju człowiekowatych). Matematyczny model dynamiki ewolucyjnego rozwoju języka (Nowak, Komarova) pokazał, że przejście z proto-języka, w którym nie było jeszcze części mowy stało się opłacalne gdy słownik człowiekowatych przekroczył 400 elementów (ze składnią przy tej wielkości słownika mówi się szybciej i bardziej precyzyjnie). Fascynują nas właśnie takie badania i analizy – wiedza dotycząca początków mowy pomaga nam zrozumieć to, z czym pracujemy na co dzień. Możemy np. postawić pytanie – jakie było pierwotne zastosowanie aktów mowy – czy ważniejsze było działanie i współdziałanie, czy może tworzenie prawdziwych i rzetelnych reprezentacji na temat świata. Z tym dylematem pracujemy niemal w każdym raporcie – a uczestnicy naszych szkoleń dzielą się na tych, którzy traktują swój język jak użyteczne narzędzie do działania i tych, bardziej upartych którzy dużo większe znaczenie przywiązują do możliwego dzięki językowi opisowi świata.

B. Badania neurolingwistyczne

Jak wytłumaczyć fakt, że mysz z wszczepionym genem FOXP2 skuteczniej radzi sobie z poznawaniem nowego labiryntu? Jakie znaczenie mają dla języka podwyższone zdolności powtarzania tych samych procedur i nawyków? Czy jest możliwa utrata czytania, ale nie pisania i czy można stracić mówienie czasownikami i zachować posługiwanie się rzeczownikami. Odpowiedzi na te pytania mogą być zaskakujące.

- FOXP2 – to gen odkryty w 7 chromosomie człowieka, którego brak odziedziczony zgodnie z prawami Mendla, powoduje zaburzenia językowe (SLI) – szczególnie w aspekcie posługiwania się gramatyką, która jest zbiorem reguł i rutyn językowych.

- Tak, w wyniku udaru można utracić zdolność czytania i zachować zdolność pisania.

- Tak, można również mieć poważne trudności w mówieniu czasownikami i dużo dużo mniejsze w posługiwaniu się rzeczownikami.

Wiedza z tego zakresu pomaga nam zrozumieć, z czym mogą wiązać się małe specyficzne błędy w mówieniu i pisaniu. Jakie znaczenie dla codziennej organizacji pracy mogą mieć istotne agramatyzmy i paragramatyzmy.

C. Rozwój języka małego dziecka

To szczególnie fascynujący obszar wiedzy ponieważ mówi nie tylko o rozwoju języka, ale także o rozwoju całego człowieka. Z naszej perspektywy dwa zagadnienia wydają się szczególnie interesujące:

Rozpad „holofraz” małego dziecka np. holofrazy „Buty!” na strukturę predykatywno-argumentową i wszystkie części mowy oraz formy fleksyjne tj. w tym wypadku:

W analizowanych przez nas transkryptach rozmów i wypowiedzi dostrzegamy różny poziom rozpadu – tylko część z nas potrafi płynnie posługiwać się złożonymi pojęciami abstrakcyjnymi, a jeszcze mniej zdaje sobie sprawę z ich ograniczeń i błędów, w które wpadamy, jeżeli je absolutyzujemy.

Rozwój teorii umysłu innych osób. Przeprowadźmy krótki test fałszywych przekonań. Do pokoju zapraszamy dwójkę dzieci. Kiedy są razem chowamy zabawkę do szafy. Teraz prosimy jedno z dzieci o wyjście z pokoju. Kiedy dziecko zamknie za sobą drzwi, wyjmujemy zabawkę z szafy i ukrywamy ją w biurku. Teraz pytamy dziecko, które widziało co robimy (i które jest badane), gdzie jego/jej kolega/koleżanka będzie szukał zabawki, kiedy ponownie zaprosimy go do pokoju. Dzieci, które odpowiedzą, że będzie jej szukał/szukała w biurku nie mają TEORII UMYSŁU INNEJ OSOBY. Takie odpowiedzi klasyfikujemy jako autystyczne. Jaki jest świat osoby, które nie potrafi przyjmować perspektywy innych? W jakim świecie żyje? Czym będzie w tej sytuacji empatia? Choć może to zabrzmieć paradoksalnie wielu z nas ma poważne trudności z decentracją (co nie oznacza oczywiście, że nie rozwiążemy testu fałszywych przekonań) – zdarza się, że nie potrafimy wczuć się w naszych klientów i naszych pracowników – często mówimy swoje i do siebie.

D. Psycholingwistyka

Z perspektywy naszej pracy istotne są:

Listy wyrażeń i wyrazów pierwotnych tj. takich, które powtarzają się we wszystkich językach świata. Ciekawe w tym kontekście może być ustalenie Swadesha, że możemy wyróżnić listę 100 takich słów, ale już nie 200, ponieważ w części języków nie będą one miały swoich odpowiedników,

Banki mowy i listy frekwencyjne współczesnej polszczyzny, w których możemy zweryfikować częstość występowania poszczególnych słów,

Teorie i badania z zakresu gramatyki generatywno-transformacyjnej (Gramatyki Uniwersalnej) opisujące funkcje i znaczenie poszczególnych części mowy oraz form fleksyjnych,

Teoria aktów mowy sformułowana przez Johna Austina i rozwijana przez Johna Searle. W niej znajdujemy zestawienia i listy czasowników performatywnych tj. wyróżniających w naszej komunikacji takie wypowiedzi jak: informowanie, zaprzeczanie, pytanie, rozkazywanie, proszenie, obiecywanie, gratulowanie, grożenie, przepraszanie, dziękowanie, mianowanie, ogłaszanie itd. Przygotowywane przez nas analizy wypowiedzi sa pełne tego typu zachowań. I ma tutaj oczywiście znaczenie czy rozmowa z zespołem odbywa się poprzez takie czasowniki performatywne jak: pytania, przekazywanie informacji czy też na przemian prośby, groźby i zastraszanie. Bardzo wielu menedżerów w ograniczony sposób korzysta z zadawania pytań i parafrazowania wypowiedzi swoich pracowników i współpracowników.

Metody analizy słów-kluczy. Np. Istotna nadreprezentacja wyrażeń: zawsze, nigdy, trzeba, powinno się, nie wolno, wszyscy, nikt, całkowicie, absolutnie, bez wątpienia zgodnie z badaniami Suitberta Ertela świadczy o podwyższonym lub wysokim poziomie dogmatyzmu. A każdy z nas wie jak trudno jest pracować z ludźmi, którzy sa nieomylni i wszystko wiedzą lepiej.

Teorie i metody z zakresu analizy dyskursu i narracji.

E. Filozofia

Nasi ulubieni autorzy to: Wittgenstein I, Wittgenstein II, Gadamer, Chomsky, Popper, Khun, Buber, Levinas.

Action Logic

Manager development programme

Action logic

models of adult human development, stages and crises

A. Different Action Logics

In our work, we meet people characterised by extremely different Action Logic. Some think almost exclusively about themselves and what is most important to them: they destroy motivation, commitment, joy and optimism around themselves. Others can listen, understand and surround their team with a special kind of care: if they can lead others, they become effective leaders in their communities.

We deal with „what and how these people talk” and „what we can read from their emotional expressions”.

B. Whitefox Method

In order to prepare a reliable DC report, we record and analyse statements, carefully (sometimes repeatedly) watching the same video records with facial expressions and using modern systems and technologies. The language and emotional expressions of egocentric people and empathic people are very different (other language forms, other facial expressions). Certainly, the world that we observe does not consist only of black and white characters: there are many shades of grey. There are at least several intermediate levels on the scale from egotism to decentration.

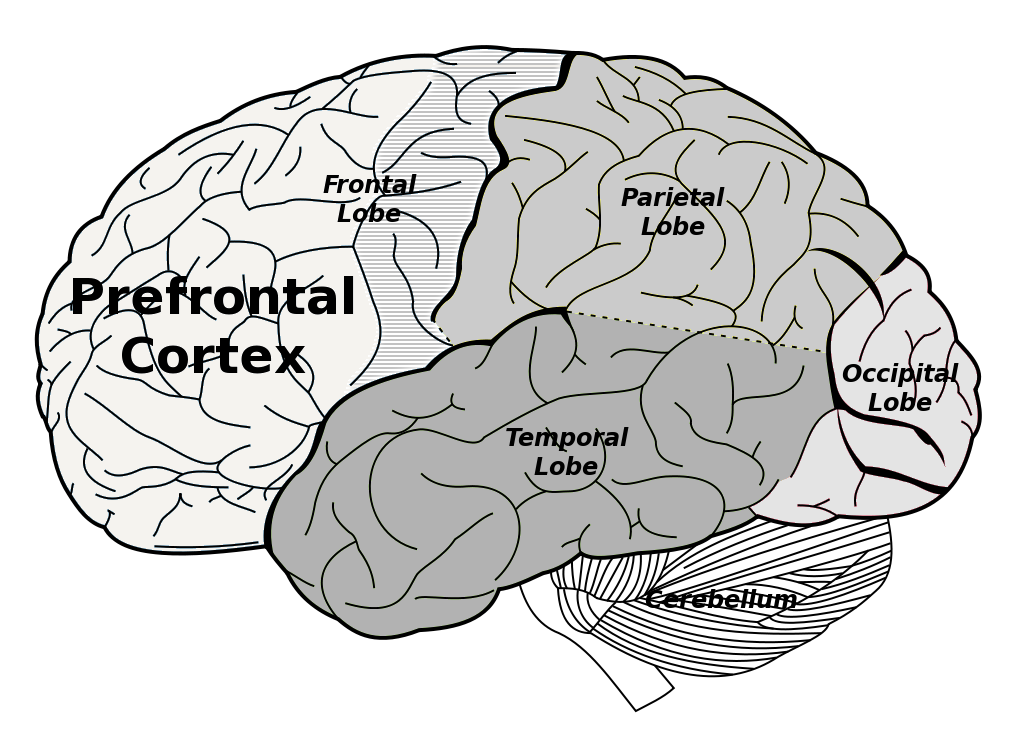

To systematise different Action Logics and communication, we use models of adult human development and neuroscientific discoveries.

C. Report and training

In our individual reports, we present the language forms and mimic patterns that characterise particular levels of listening and understanding and the neural structures that take part in described communication processes. Participants of our training and development programmes most often say that the experience of seeing themselves from the perspective of these analyses helps them change and develop, and practising new language forms during the training deepens this experience.

Below, we present descriptions of 6 levels of leadership inspired by the Torbert’s model (Global Leadership Profile) and selected neural structures involved in the communication process.

AI – arterior insula

Amyg – amygdala

cACC/MCC – caudal anterior cingulate cortex, midddle cingulate cortex

dMPFC/vMPFC- dorsal et ventral medial prefrontal cortex

FO – frontal operculum

IFG – inferior frontal gyrus

IPL, IPS – inferior parietal lobule, inferior parietal sulcus [mirror neuron]

OFC – orbifrontal cortex

pSTS – posteriol superior temporal sulcus

RTPJ – right temporal-parietal junction

SMC – sensory-somatic cortex

Emotions and motivation

Analysis of facial expressions

Emotions and motivation

facial action coding system, Paul Ekman 70'

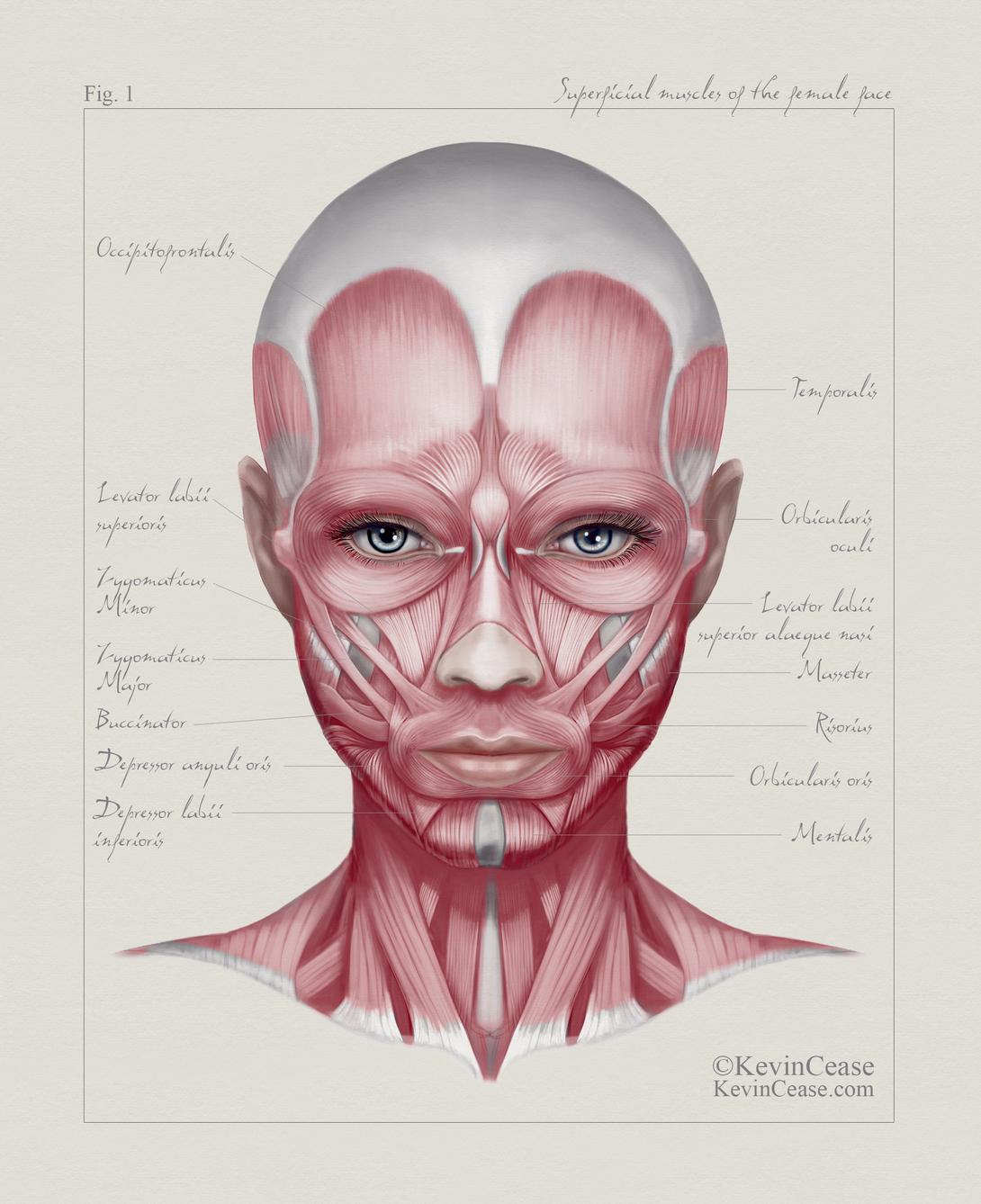

The Facial Action Coding System was published by Paul Ekman and Wallace Friesen in Facial Action Coding System: A Technique for the Measurement of Facial Movement in 1978. This publication has forever changed the modern way of thinking about emotions and the approach to their recognition and research. The key assumption of the authors was the empirically confirmed thesis that human emotions were innate and universal, i.e., independent of the place on earth; people, as representatives of the same species, experience emotions that manifest themselves in the same facial expressions (people from different cultural backgrounds were examined, also those that had never had any contacts with the Western civilization before). In the final version of the system, Ekman distinguished 7 emotions that he called the basic ones. These include: happiness, sadness, surprise, fear, anger, disgust and contempt.

It turns out that regardless of what language we speak and what standards of behaviour have been instilled in the process of our education, we show happiness, sadness, anger, etc. in a similar way. Subsequent research has shown that the universality of emotions also applies to those blind since birth and even children in mother’s womb in which, about 6 months of age, you can notice the first facial expressions of joy and disgust. The fact that our face betrays authentic emotions and, consequently, intentions and attitudes has almost instantly become the subject of special interest of all professionals whose daily work is directly related to reading human emotions (employees of marketing and HR departments, psychologists, policemen, employees of intelligence agencies). From our perspective, skills related to the accurate recognition of emotional states of others will have critical meaning for everyone working in sales, customer service and, of course, those whose most important role is to manage others.

During our training and courses, according to Paul Ekman’s guidelines, we practice four basic skills:

- Mindfulness of emotions that arise within us before we even begin to speak or do something,

- Conscious control over selection of own behaviour in order to be able to achieve goals important for us without harming others,

- Recognition of emotions in others based on subtle movements of facial muscles, body posture and tone of voice,

- Caution in using the information obtained this way in relation to feelings of other people.

To practice and master the accuracy of reading facial expressions, we use computer software developed based on a manual analysis of 10,000 photographs depicting the above-mentioned emotions. The application creates a face grid composed of 500 key points that enable to monitor the movements of individual muscles.

m.jarzmowy większy

AU 12: Zygomaticus major

Wyraźne unoszenie kącika ust - uśmiech i pogarda

m.policzkowy

AU 14: Buccinator

Obniżanie kącika ust - pogarda

m.okrężny ust

AU 23: orbicularis oris

Rozciąganie i zaciskanie ust (kreska) - gniew

7 basic emotions

17 face muscles

Facial Acion Coding System (AU)

Happiness: 6+12; Sadness: 1+4+15; Surprise: 1+2+5B+26;

Fear: 1+2+5+20+26; Anger: 4+7+20; Disgust: 9+15+16;

Contempt: R12A+R14A

AU 1 – frontal muscle (middle part) – Raising the inside of the eyebrows

AU 2 – frontal muscle (lateral part) – Raising the outside of the eyebrows

AU 4 – procerus muscle, depressor supercilii muscle, corrugator supercilii muscle – Lowering the eyebrows

AU 5 – elevating muscle of upper eyelid, superior tarsal muscle – Raising the upper eyelids

AU 6 – orbicularis oculi (pars orbitalis) – Raising the cheeks

AU 7 – orbicularis oculi (pars palpebralis) – Closing the eyelids

AU 9 – levator labii superioris alaeque nasi – Wrinkling the nose

AU 12 – zygomaticus major – Raising the corner of the lips (clear)

AU 14 – buccinator – Smile with lowered corners

AU 15 – depressor anguli orist – Lowering the corner of the lower lip

AU 16 – depressor labii inferioris – Lowering the lower lip

AU 20 – risorius – Stretching the lips

AU 23 – orbicularis oris – Lip stretched and tightened (line)

AU 26 – masseter; relaxed temporalis and internal pterygoid – Jaw dropping

The analysis of the above-mentioned movements of facial muscles allows the accurate recognition of the emotional state of the person or persons we are currently talking to. Whitefox is particularly interested in all the permanent stiffening of facial muscles and other muscles throughout the entire body. A trained mask of indifference, an artificial smile, withheld rage and anger, or suspension of the body in a hook-, column-, hanger- or halter-like shape tell us about the history and specific difficulties in dealing with negative emotions. Understanding the importance of tensions and stiffeners and their mitigation brings relief and supports overstepping the limits of the preferred logic of action and motivations currently in force.

AU6

AU12

Happiness 6 + 12

Action Unit 6: Raising the cheeks; Action Unit 12: Raising the corner of the lips

The expression of happiness is a signal that we experience pleasure, amusement, relief, peace, satisfaction, pride or excitement. By being happy, we tell others that what is happening “is good and we encourage them to come into contact with us and be together” (Paul Ekman). In our work, we meet many angry, sad and frightened people. We rarely see joy on their faces. The constant message to others: “I am unhappy; I am scared; you upset me; I will do something to you soon” makes our colleagues and employees want to avoid us; they will not pass information on to us; they will not talk about their problems or ideas. Many people we work with do not realise the huge professional potential hidden in the job that gives you satisfaction and allows you to be a “cheerful person”.

AU1

AU4

AU15

Sadness 1 + 4 + 15

Action Unit 1: Raising the inside of the eyebrows; Action Unit 4: Lowering the eyebrows; Action Unit 15: Lowering the corner of the lower lip (lips turned down)

Sadness is a reaction to loss and a signal to others that we need support and care. When we become sad, we are saying to others: “I have lost something important to me: comfort me.” It happens that we meet people whose difficult professional and private issues have taken away their optimism, hope, energy for work and faith in others. Our actions in such situations focus on training the skills that enable them to experience sadness in the context of the whole life history and together with their close ones who often wait for many years to deal with their pain. During training, we also teach managers and leaders how they can, in their roles, help others deal with this difficult feeling.

AU1

AU2

AU5B

AU26

AU26

Surprise 1 + 2 + 5B + 26

Action Unit 1: Raising the inside of the eyebrows; Action Unit 2: Raising the outside of the eyebrows; Action Unit 5B: Raising the upper eyelids (slightly); Action Unit 26: Jaw dropping

“Surprise is the shortest of all emotions. It lasts up to a few seconds. After a while, when we know what is happening, surprise turns into fear, amusement, anger, disgust, etc., depending on the surprise we are dealing with”. (Paul Ekman). This short-lasting emotion is especially important when recognising a lie. We are hardly ever good at pretending to be surprised. During the training in the field of communication, negotiations and B2B sales, we teach how to use subtle movements of facial muscles to recognise when someone is trying to cheat us.

AU1

AU2

AU5

AU20

AU26

Fear 1 + 2 + 5 + 20 + 26

Action Unit 1: Raising the inside of the eyebrows; Action Unit 2: Raising the outside of the eyebrows; Action Unit 5: Raising the upper eyelids; Action Unit 20: Stretching the lips; Action Unit 26: Jaw dropping

Fear appears in emergency situation and tells others: “help me”. This is a reaction to the possibility of physical or mental pain. We often feel fear during public appearances, before talking to our boss who does not control his anger, during audits strategic for the company or when we see that we will probably not achieve the set goals and will experience the related consequences. Fear destroys our effectiveness in dealing with difficult situations if it causes only paralysis and panic.

AU4

AU7

AU23

Anger 4 + 7 + 20

Action Unit 4: Lowering the eyebrows; Action Unit 7: Closing the eyelids; Action Unit 20: Lips stretched and tightened (in a line)

Anger is a reaction to a barrier/obstacle or a situation in which we think that we are being treated unfairly. When you get angry, you tell the other person: “get out of my way”. Anger differs from other emotions in that it creates the greatest threat to others. Constant control, constant irritability, outbursts of anger and, finally, wrong personnel decisions – all this makes us a threat to our team. The pressure we experience makes it harder and harder to accept other people’s perspective and understand their needs. During our training, we show the exercises that prevent from plunging into behaviour leading directly to psychopathy, narcissism and borderline.

AU9

AU15

AU16

Disgust 9 + 15 + 16

Action Unit 9: Wrinkling the nose; Action Unit 15: Lowering the corner of the lower lip; Action Unit 16: Lowering the lower lip

Disgust can occur in response to tastes, smells, tactile impressions, thoughts, views, sounds, other people, actions of these people, and even in relation to ideas (Paul Ekman). As we wrinkle our nose, we tell others: “stay away from this, take it away from here”. The expression of disgust is of particular importance to us when designing and implementing focus group interviews (especially in the food industry). It is also a serious warning signal if it appears many times during team work. Diagnostic peculiarity: “the expression of wife’s disgust addressed to her husband during a conversation in which both of them were to resolve a conflict proved to predict how much time the couple would spend separately in the next four years. Wife’s disgust usually appeared in response to her husband’s withdrawal”. (Gottman, 2001).

R12AU

RAU14

Contempt R12A + R14A

Action Unit R12A: Raising the corner of the lips; Action Unit R14A: Smile with lowered corners

“We feel contempt only for people and their behaviours, not for tastes, smells or tactile sensations. […] Disrespectful aversion to people or their behaviours makes us feel better from them”. (Paul Ekman). The most important function of contempt is to signal a sense of superiority, strength and a higher status. Paradoxically, this emotion most often appears on the faces of people who are uncertain of their position and value, but who want to be seen as extremely intelligent, educated, extremely hard-working, often very family-oriented. If a contemptuous smile becomes a fixed element of our facial expressions, it is very difficult to build relationships with others. Customers, colleagues and employees sense this “bizarre” sense of superiority (they distance themselves and laugh).

Strategy and innovation

Psychologia języka

Strategie i innowacje

narracja i paradygmaty, rachunek zdań, części mowy, formy fleksyjne

Kiedy ktoś zwraca się do nas po indywidualną pomoc rozpoczyna najczęściej od przedstawienia krótszych lub dłuższych opowieści, które wiążą się dla niego z lękiem, smutkiem, wyczerpaniem lub złością. W czasie rozmów poznajemy szczegółowo kolejne zdarzenia, bohaterów i konsekwencje tych historii. Wiele z tych opowiadań, w sytuacjach kryzysowych, kończy się formułowaniem następujących ocen:

- Jestem do niczego. Jak mogłem/mogłam doprowadzić do takiej sytuacji. Jeśli pozwoliłem/pozwoliłam, aby coś takiego się stało musi być ze mną coś nie tak. Zepsułem/Zepsułam wszystko!

- Nie poradzę sobie. To, co chciałbym/chciałabym lub muszę zrealizować jest ponad moje siły. Moja historia w tym obszarze to wyłącznie ciąg porażek i błędów. Nic mi już nie pomoże! Nadzieja to jedynie oszukiwanie siebie.

- Nie zasługuję na: szacunek, przyjaźń, miłość.

- Jestem złym człowiekiem. To, co zrobiłem/zrobiłam świadczy o tym, że myślę wyłącznie o sobie. Jestem nic nie wartym/wartą egoistą/egoistką!

- Moje życie jest żałosne! Powinienem/powinnam być najbardziej samotnym człowiekiem na świecie.

- Świat jest wrogim miejscem w którym każdy myśli tylko o sobie. Też będę tak robił/robiła.

Czasami wypowiadamy to wszystko wprost. Czasami tak myślimy i nie mówimy o tym innym. Zdarza się też, że tylko niejasno rozpoznajemy, że żyjemy w więzieniu zbudowanym z własnych ocen i strachów. Przemijamy zamknięci w naszych oskarżeniach. Zaklęci w żabę ograniczamy marzenia. Sami siebie sądzimy, sami siebie skazujemy, sami sobie wymierzamy karę samotności i wewnętrznej pogardy lub decydujemy się na życie w świecie, w którym najważniejszym doświadczeniem jest samotność

Na szczęście tak bywa tylko w sytuacjach kryzysowych. Nie jest to czas łatwy, ani bezpieczny. Kiedy cierpimy, boimy się, złościmy, przeżywamy osamotnienie nasze historie układają się w złe bajki i mity, które chciałyby nas przerobić na swoich bohaterów.

Rozbicie tych ciemnych historii zaczyna się często od zadania pytań, które pozwalają zobaczyć, że to na czym skupiła się nasza pamięć i uwaga to jedynie wycinki rzeczywistości tendencyjnie ułożone w złą opowieść. Z opisu ubogiego i rozrzedzonego przechodzimy do opowiadania bogatego i złożonego. Nazywamy nasze trudności, aby móc uwolnić się od ich wpływu. Przytaczane są inne pomijane fakty i zdarzenia. Pojawiają się nowi bohaterowie, którzy do tej pory milczeli lub byli niezauważeni. Historia opowiadana jest raz jeszcze – od nowa – uzupełniona o dobre relacje, w których mówimy i myślimy o powodzeniu, o radzeniu sobie, o własnej kompetencji i wartości, o szacunku do siebie, o radości, o przyjaźni, o pięknie, o miłości.

Language forms

Psychology of language

Language forms

narrative and paradigms, propositional calculus, parts of speech, inflectional forms, foxp2

What is said is one of the most specific manifestations of our thoughts, attitudes and preferred ways of action: it can be recorded, written down and subjected to a reliable and precise quantitative and qualitative analysis. Studying language is our passion and the most basic method of work. Let’s move to a few examples.

Comments to your statements in individual reports and communication tips provided during training courses usually refer to the fields of knowledge and language sciences listed below. Here, we would like to list only the most important ones.

A. Anthropology and beginnings of speech development

Hominidae: 99% development without language

It is assumed that the language as we know it, i.e. based on the syntax, was created about 45,000 years ago with the appearance of the new species, Homo Sapiens. With 6 million years of development of hominids, speaking is something really new (it involves less than 1% of the development time for humans). The mathematical model of evolutionary dynamics of language development (Nowak, Komarova) has shown that the transition from the proto-language in which there were still no parts of speech became beneficial when the vocabulary of humans exceeded 400 components (a syntax with a vocabulary of this size could be used faster and more precisely) . Indeed, we are fascinated by such research and analyses: knowledge about the beginnings of speech helps us understand what we work with every day. We can, for example, ask what was the original use of acts of speech; whether action and collaboration were more important, or was it perhaps creating real and reliable representations about the world? We face this dilemma in almost every report, and participants of our training courses can be divided into those who treat their language as a useful tool for action, and those more stubborn who attach much greater importance to the description of the world made possible thanks to language.

B. Neurolinguistic research

How to explain the fact that mice with an implanted FOXP2 gene are more effective becoming familiar with a new maze? What is the significance of increased ability to repeat the same procedures and habits for language? Is it possible to lose reading, but not writing skills, and is it possible to lose the ability to speak using verbs, but keep the ability to use nouns? Answers to these questions can be surprising.

- FOXP2 is a gene discovered on human chromosome 7 the lack of which, inherited in accordance with Mendel’s law of heredity, causes specific language impairment (SLI), especially in the aspect of using grammar, which is a set of rules and language routines.

- Yes, you can lose the reading ability and retain your writing ability as a result of a stroke.

- Yes, you can also have serious difficulty speaking in verbs and much less using nouns.

Knowledge in this respect helps us understand what results in small specific mistakes in speaking and writing. What the meaning of significant agrammatism and paragrammatism may be for everyday organisation of work.

C. Language development in small children

This is a particularly fascinating area of knowledge because it involves not only the development of language, but the development of the entire person. From our perspective, two issues seem particularly interesting:

The decomposition of “holophrases” of small child, e.g. „Shoes!” into a prediction/argument structure and all parts of speech and inflectional forms, i.e. in this case:

In the transcripts of conversations and statements that we analyse, we see a different level of decomposition: only some of us can fluently use complex abstract concepts, and we are even less aware of their limitations and the mistakes we make if we absolutise them.

Development of theory of other people’s mind. Let’s conduct a short test of false beliefs. Two children are invited into a room. When they are together, we hide the toy in a wardrobe. Then, we ask one of the children to leave the room. When the child closes the door behind him/her, we take the toy out of the wardrobe and hide it in a desk. We are now asking the child who witnessed what we did (and who is tested) where his/her colleague will look for a toy when we invite him/her back into the room. The children who will answer that the other child will be looking for the toy in the desk do not have the THEORY OF OTHER PEOPLE’S MIND. We classify such responses as autistic. What is the world of a person who cannot take other people’s perspective? What world does he/she live in? What is empathy in this situation? Although it may sound paradoxical, many of us have serious difficulties with decentration (which does not mean, of course, that we will not solve the test of false beliefs): it happens that we cannot empathise with our customers and employees; we often speak what we are convinced of and often to ourselves.

D. Psycholinguistics

The following are important from the viewpoint of our work:

Lists of primal expressions and words i.e. those that are repeated in all languages of the world. Swadesh’s finding may be interesting in this context: that we can distinguish a list of 100 such words, but not 200 because in some languages there will be no equivalents,

Speech banks and frequency lists of the contemporary Polish language in which we can verify the frequency of individual words,

Theories and studies in the field of generative-transformational grammar (Universal Grammar), describing functions and meaning of particular parts of speech and inflectional forms,

Speech act theory formulated by John Austin and developed by John Searle. It features lists and breakdowns of performative verbs, i.e. those that distinguish such statements in our communication as: informing, denying, questioning, ordering, asking, promising, congratulating, threatening, apologising, thanking, appointing, announcing, etc. Our analyses of statements are full of this type of behaviour. Here, of course, it is important whether or not a conversation with the team involves such performative verbs as: questioning, transferring information or, alternately, asking, threatening and intimidating. A lot of managers uses questions and paraphrasing of statements of their employees and associates to a limited extent.

Methods to analyse key words. E.g.: Significant overrepresentation of statements: always, never, should, need, must not, everyone, no-one, totally, absolutely, undoubtedly, according to Suitbert Ertel’s studies shows an elevated or high level of dogmatism. Each of us knows how difficult it is to work with people who are infallible and know everything better.

Theories and methods in the field of discourse and narrative analysis.

E. Philosophy

Our favourite authors include: Wittgenstein I, Wittgenstein II, Gadamer, Chomsky, Popper, Khun, Buber, Levinas.